A four-month exhibition, of huge scope, at London’s National Gallery.

Van Gogh, “Woman from Arles.”

I always want to perceive how a thing was done, which mainly means the order of the actions. This picture, like many, was both drawn and painted: there are outlines, and there are filled areas, both done with brushes and paints. But in which order? At first it looks as if Van Gogh scrubbed on large areas and then drew boundaries within and around them; and that could be so with the face. But when you look closely you see that area-filling paint laps onto and over the outlines in places such as the elbow resting on the table, and the left horizon of the pages of the upper book.

When Vincent painted this portrait and five other versions of it, he wasn’t looking at Madame Ginoux, proprietor of the Café de la Gare, but at a drawing of her by Paul Gauguin, left behind by that domineering man when he broke off his 1888 visit to Arles and his vulnerable friend.

Art pundits generally talk of abstractions rather the how-to. But the plaque beside this picture says interestingly: “Gauguin had argued for finding the essence of a subject by working from memory, an idea that Van Gogh resisted at the time. But here… Van Gogh acknowledges the potential of Gauguin’s approach.” In other words, by looking only at the drawing and at the image carried away from the café in his head, he could more freely paint the “idea” of the woman, undistracted by her live and mobile presence.

Balzac’s novels are a universe. That was why I lingered at Rodin’s “Monument to Balzac.” What is it made of? You can see it isn’t hacked from stone: the foot overlaps the plinth. It is the plaster model, from which (after Rodin’s death) was cast the bronze that now stands in Paris. You can imagine the sculptor’s hand delving into that hanging fold in the drapery.

Théo van Rysselberghe, “The Scheldt Upstream from Antwerp, Evening,” 1892.

This picture was used to advertize the show. And the scene asks for pointillism: atomizing of colors by the twilight and by the dimpled water. Then the posts inject contrast.

To make each long left-to-right sub-discernible ripple, the painter mixes a slightly darker blue, then keeps it constant on the brush tip while jabbing a hundred dots along a disciplined horizontal path, perhaps aided by that instrument – I’ve forgotten what it’s called – a long ruler that makes a bridge on which to rest the hand.

I sort of don’t approve of pointillism – it, and Leonardo’s sfumato or “smoky” smoothed style, are far removed from bold painterly brushwork. But Signac’s pine tree is undoubtedly attractive. Pretty. Besides, the name “Signac” is pretty.

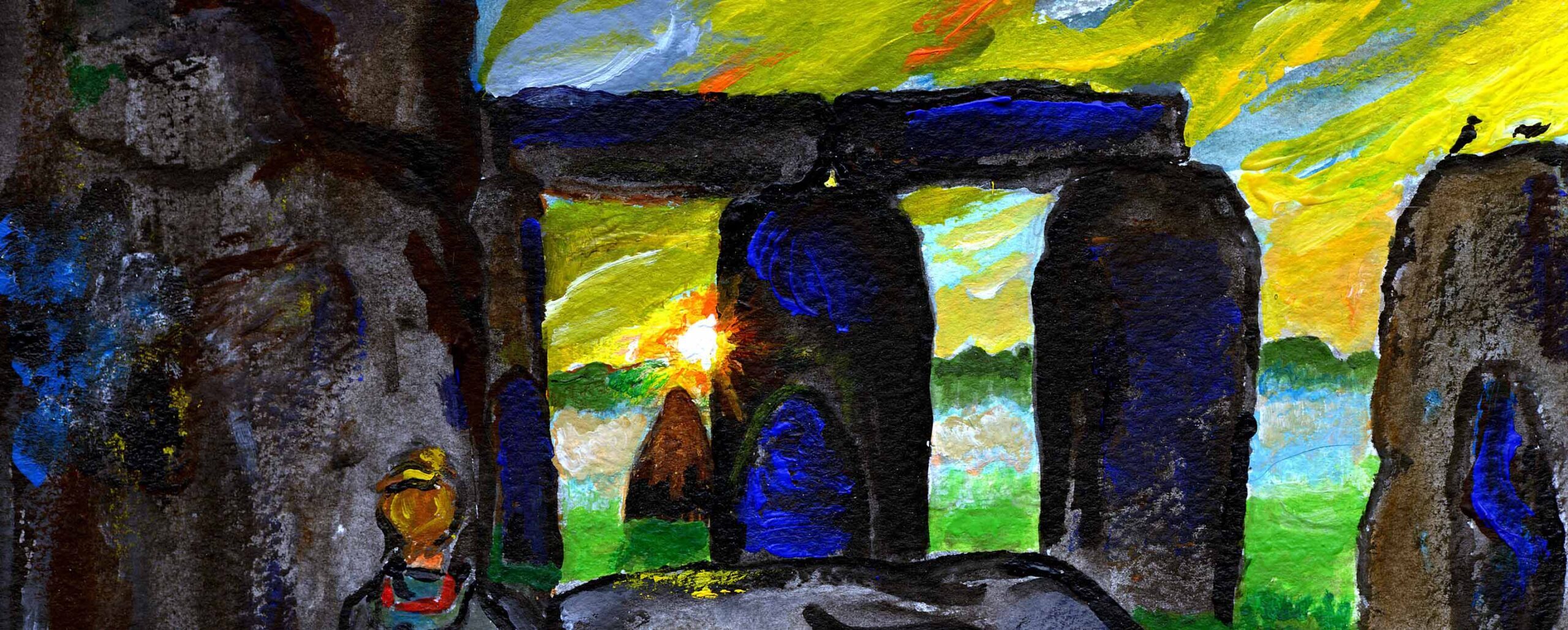

André Derain, “The Dance,” 1906.

Probably the whole was covered with the gold of the sky; then the drawing was made, with a dark blue, we’ll call it indigo. Then the areas of the drawing were painted in. You can see that in the central female figure the upper line of the thigh has disappeared under the dusky red of the flesh. But then the indigo lines were carried, as if invading from the grass, onto the male figure, clothing him in a maze. And the snake is drawn as a maze, passing under the legs and feet, but its green fill in some places lapping onto them.

A name I’d never heard of, Louis Anquetin; an incredibly skilful painting, “Avenue de Clichy, Five in the Evening,” 1887.

It was prepared with the overall dull-blue of the sky, then drawn with a fine brush, then the cells of the drawing painted in.

Just to make the drawing, with controlled pressure of the brush and with hours of patience and faith, was am enormous feat, whether done on the spot, or from a sketch made on the spot, or from memory, or from memory-assisted imagination, or from a photograph – as is just possible, since the camera had been invented. Those hundreds of cells of the drawing represent the twigs against the sky, the elements of the buildings, and the dense crowd, including figures seen deep through crevices in it. Then Anquetin chose color after color – working, I think, from the right, and using a variety of brushes – to fill cells so that light grades fracturedly from the doorway through the crowd to the night. Is stare-time a measure of merit in a piece of art – one’s willingness to keep looing at it and noticing more?

__________

This weblog maintains its right to be about astronomy or anything under the sun.

ILLUSTRATIONS in these posts are made with precision but have to be inserted in another format. You may be able to enlarge them on your monitor. One way: right-click, and choose “View image” or “Open image in new tab”, then enlarge. Or choose “Copy image”, then put it on your desktop, then open it. On an iPad or phone, use the finger gesture that enlarges (spreading with two fingers, or tapping and dragging with three fingers). Other methods have been suggested, such as dragging the image to the desktop and opening it in other ways.

I am not knowledgeable in the field of art, so I can’t make informed statements about any of the paintings or techniques used by the artists you highlighted, but I did take note of your lack of enthusiasm regarding pointillism. I just received the three AstroCal back issues (1974 – 1976) I ordered last week, so thank you very much for the opportunity to complete my collection. In the 1976 issue, for the first time you employed a pointillist technique for rendering the Milky Way in your monthly charts, which I believe you used until the early 1990’s. I always regarded that method as the most authentic and persuasive way of portraying the subtle glow of the galaxy, especially the way you faded it out at the edges by using fewer dots. I’m sure that was a time consuming process!

Good point, the Milky Way is a supreley pointillist object, indeed the whole starry sky is! But many times when you see an illustration, such as a cartoon, that has areas filled with dots – such a my Portrait of a Million – it’s been done by laying on a manufactured preprinted sheet, or, nowadays, by even easier electronic means.

It is a fascinating picture by Anquetin, capturing Parisian nightlife, and the relatively new use of gas lamps, with the contrast of bright yellow light and dimmer blue city-scape. Often with photos the places in the distance appear smaller than with naked eye so maybe this was made from a sketch, not a photo. Also, many post-impressionist paintings use dark outlines in all parts of the picture, which may have come from seeing Japanese prints in Europe in the 1870s and afterwards? Any insights on the dark outlines? I like them, they make it less “realistic”. Thanks

Guy there is also an underlying layed out perspective in the Anquetin painting setting the great depth of field.

Yes, all the way from the cropped foreground figure through the buildings that are almost part of the sky.